Convincing Millennials to 'Marry a Nice Jewish Boy'

Confronted with an unprecedentedly secular crop of young people, Jewish leaders are pushing intra-religious marriage harder than ever. Their favorite approach? Youth groups.

An acquaintance gave a few of us a ride after the annual post-Yom Kippur feast. Stuffed with bagels, lox, kugel, and every kind of pound cake imaginable, the four of us chatted happily about life in D.C., past trips to Israel, and guilt over skipping religious services earlier that day.

And then the conversation turned to dating.

“Would you ever marry a non-Jew?” Sharon asked from the backseat. Answers varied; one person said she wasn’t sure, while another said she might consider marrying someone who was willing to convert. Debates about intermarriage, or marriage outside of the faith, are common in the Jewish community, but her question still struck me as remarkable. Here were four twentysomething women who hardly knew each other, already talking about the eventuality of marriage and apparently radical possibility that we would ever commit our lives to someone unlike us. This conversation seemed very “un-Millennial”–as a whole, our generation is marrying later, becoming more secular, and embracing different cultures more than any of our predecessors. If the same question had been asked about any other aspect of our shared identities–being white, being educated, coming from middle or upper-middle class backgrounds—it would have seemed impolite, if not offensive.

Although many religious people want to marry someone of the same faith, the issue is particularly complicated for Jews: For many, faith is tied tightly to ethnicity as a matter of religious teaching. Jews do accept conversion, but it's a long and difficult process, even in Reform communities—as of 2013, only 2 percent of the Jewish population are converts. Meanwhile, the cultural memory of the Holocaust and the racialized persecution of the Jews still looms large, making the prospect of a dwindling population particularly sensitive.

The lesson, then, that many Jewish kids absorb at an early age is that their heritage comes with responsibilities—especially when it comes to getting married and having kids.

In large part, that’s because Jewish organizations put a lot of time and money into spreading precisely this message. For the Jewish leaders who believe this is important for the future of the faith, youth group, road trips, summer camp, and online dating are the primary tools they use in the battle to preserve their people.

Youth Group, the Twenty-First Century Yenta

Although Judaism encompasses enormous diversity in terms of how people choose to observe their religion, leaders from the most progressive to the most Orthodox movements basically agree: If you want to persuade kids to marry other Jews, don’t be too pushy.

“We try not to hit them over the head with it too frequently or too often,” said Rabbi Micah Greenland, who directs the National Conference of Synagogue Youth (NCSY), an Orthodox-run organization that serves about 25,000 high school students each year. “But our interpersonal relationships are colored by our Judaism, and our dating and marriage decisions are equally Jewish decisions.”

On the opposite end of the spectrum of observance, a Reform organization, the North American Federation of Temple Youth (NFTY), seems to take a similar tack, especially in response to frequent questions from donors and congregants about intermarriage trends. “Our response to [concerns about] intermarriage is less to have conversations about dating—we want to have larger conversations about what it means to be Jewish,” said the director of youth engagement, Rabbi Bradley Solmsen, who estimated that NFTY serves about 17,700 Jewish students each year.

But make no mistake: This doesn’t mean they have a laissez-faire attitude about intermarriage. In every denomination, the leaders I talked with are thinking intentionally about how to strengthen the sense of connection among teenaged Jews.

“There’s no question that one of the purposes of the organization is to keep Jewish social circles together at this age,” said Matt Grossman, the executive director of the non-denominational organization BBYO, which serves about 39,000 American students each year.

“If they’re in an environment where their closest friends are Jewish, the likelihood that they’re going to end up dating people from those social circles, and ultimately marry someone from those social circles, increases dramatically,” Grossman said.

Organizations like Hillel, a non-denominational campus outreach organization, have gathered data on the most efficient ways of encouraging these friendships. “If you have students reaching out to other students to get them involved in Jewish life, and when an educator is paired with them, they end up having more Jewish friends than your average student,” said Abi Dauber-Sterne, the vice president for “Jewish experiences.”

Summer camp is also effective at building Jewish bonds. Rabbi Isaac Saposnik leads a camp for Reconstructionist Jews, who are part of a newer, progressive movement to reconnect with certain Jewish rituals while remaining modern. He spoke about his movement’s effort to expand their tiny youth programs, which currently serve around 100 students each year. “The focus went first to camp, because the research shows that that’s where you get—and I don’t love this phrase—the biggest bang for your buck.”

For the most part, organizations have seen a remarkable “bang.” Rabbi Greenland reported that of the NCSY alumni who married, 98 percent married a Jew. According to a 2011 survey BBYO took of its alumni, 84 percent are married to a Jewish spouse or living with a Jewish partner. “These bonds are very sticky,” said Grossman.

One of the most effective incubators of Jewish marriage is Birthright Israel, a non-profit organization that gives grants to organizations to lead 18- to 26-year-old Jews on a free, 10-day trip to Israel. The organization compared marriage patterns among the people who went on Birthright and those who signed up but didn’t end up going—they got waitlisted, had a conflict, lost interest, etc. The waitlisted group is particularly large—in some years, up to 70 percent of those who sign up don’t get to go.

The difference was stark: Those who actually went on Birthright were 45 percent more likely to marry someone Jewish. This “is some kind of reflection of the experience in Israel, although there is no preaching during the ten days,” said Gidi Mark, the International CEO of Taglit-Birthright Israel. “It was astonishing for us to realize that the difference is such a huge difference.”

It’s hard to measure the success of any of these programs definitively. There’s certainly some self-selection bias at work. At least some of those who joined youth groups, went to summer camp, and traveled to Israel probably grew up in families that valued and reinforced the importance of having Jewish friends and finding a Jewish partner, so they may have been more likely to marry Jewish whether or not they participated in these activities. But even among less observant Jews, there seems to be a lingering sense that Jewish social connections are critical, especially when it comes to dating. For many, this means that after quitting youth group, waving goodbye to camp, or flying home from Israel, they still feel an obligation to consider their Judaism as they make the plunge into the dating world.

A Good Jewish Man Is Hard to Find

Outside of the built-in networks of youth groups and summer camp, if a Jew wants to date another Jew, she’ll probably try JDate. Owned and operated by Spark Networks, the same company that runs ChristianMingle.com, BlackSingles.com, and SilverSingles.com, JDate is the primary dating service for Jews (and gentiles who are particularly interested in marrying Jewish people, for that matter). According to data provided by the company, they are responsible for more Jewish marriages than all other online dating services combined, and 5 out of every 9 Jews who have gotten married since 2008 tried finding their match on the Internet.

But JDate sees itself as more than a dating service. “The mission is to strengthen the Jewish community and ensure that Jewish traditions are sustained for generations to come,” said Greg Liberman, the CEO. “The way that we do that is by making more Jews.”

Indeed, pictures of so-called “JBabies” featured prominently in promotional materials sent over by the JDate team. In JDate’s view, these new Jews will be the future of the people, but they’re also good for business. “If we’re at this long enough, if Jews who marry other Jews create Jewish kids, then creating more Jews ultimately repopulates our ecosystem over time,” said Liberman.

It’s hard to imagine this kind of language being used in other communities without provoking outrage, particularly if it was used in a racial context. But perhaps because they are so assimilated or because of their long history of persecution, Jews are given a collective pass in American culture—this casual reference to racial preservation seems almost wry and ironic. Companies like JDate use the strong association between humor and Judaism to their advantage: JBabies sounds like a punchline, where “White Babies” or “Black Babies” might sound offensive. But the company is also being serious—they want more Jewish babies in the world.

Even though it’s a private business, JDate doesn’t work in isolation – in fact, it’s strongly connected to the network of organizations that run youth groups, summer camps, and Israel trips, including the Jewish Federation. In some ways, joining JDate is the inevitable next step for teens once they leave the comfort of their temple’s youth group or campus’s weekly Shabbat services. “It’s not like a natural transition—go on a Birthright trip to Israel, come back, join JDate – but it’s not an entirely unnatural extension, either,” said Liberman.

Even for people who aren’t that interested in Judaism, which is true of at least some of the people on JDate, the site has become a cultural fixture. “At weddings, I’m very popular—I’m something of a magnet for Jewish mothers and grandmothers asking me if I have someone for their kids or grandkids,” Liberman said.

Making Jewish Babies Isn’t That Easy

But as everyone in the media has been eager to point out over the past month since the Pew study came out, these efforts aren’t without their challenges. A third of Jewish Millennials, or those who were born after 1980, describe themselves as having no religion – they feel Jewish by culture or ancestry only. Among all adults who describe themselves that way, two-thirds aren’t raising their kids with any exposure to Judaism at all.

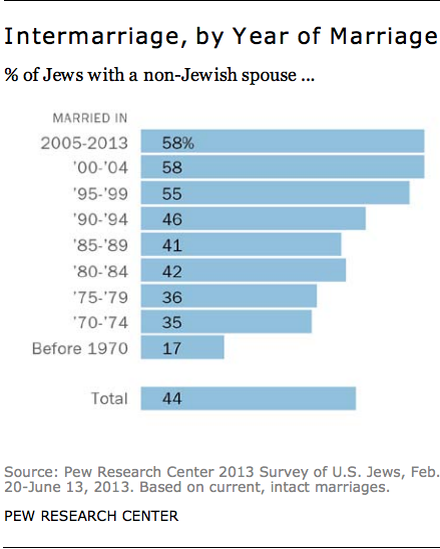

More Jews are also marrying outside of the faith. Six in ten Jews who got married after 2000 had a non-Jewish spouse, compared to four in ten of those who got married in the 1980s and two in ten of those who married before 1970. By way of comparison, other minority religious groups in America have much higher rates of marriage to one another—87 percent of Mormons and 84 percent of Muslims marry a spouse within their faith.

But even as Jewish leaders look ahead at the trends that will define the future of the Jewish population, they are thinking about how to work with the growing number of current students who were raised by intermarried parents. This is common at United Synagogue Youth (USY), a conservative organization that serves more than 12,000 students, said Rabbi David Levy, the director of teen learning. “It’s a balance of finding a way to be positive about marriages in the faith without being judgmental of the families that these teens come from,” he said.

Although there was a lot of consensus among the Jewish leaders I spoke with about how to work with teens in general, they had different ways of dealing with the tension between wanting to show openness and wanting to support Jewish marriages. Rabbi Avi Weinstein, who helps lead the campus outreach arm of the ultra-Orthodox organization Chabad, was upfront about his view that “marrying outside of the faith is one of the greatest challenges facing individual young people and the Jewish people as a collective.” Chabad, which reports that it interacts with close to 100,000 students each year, is trying to combat that trend directly. “Jewish education, both formal and especially informal Jewish education, is very effective in preventing intermarriage and in helping young people build strong Jewish identities as they mature,” Weinstein wrote in an email.

In contrast, the Reform rabbi, Bradley Solmsen, was the only person to push back against the premise that Jewish students need to be interested in heterosexual marriage at all, arguing that youth groups have to welcome LGBTQ and interfaith students alike. This points to an interesting aspect of this debate: Encouraging marriage for the purpose of Jewish procreation sets gay Jews apart from their community.

No matter how welcoming these leaders want their youth groups to be, they’re faced with data that suggest a hard truth: Jewish marriages lead to more Jewish families. According to a massive study on Jewish life in American recently released by Pew, 96 percent of Jews with a Jewish spouse are raising their children religiously, compared to only 20 percent of Jews with a non-Jewish spouse. Another 25 percent of intermarried couples are raising their kids with Jewish culture. Again, there’s a correlation versus causation question here: People who marry other Jews are likely to feel strongly about their faith already, so it makes sense that most of them would raise their kids religiously. But the comparison is still stark: Couples with two Jewish partners are about twice as likely to raise their kids with any kind of Jewish exposure.

Eric Fingerhut, the president and CEO of Hillel, summed this problem up nicely. “Living a Jewish life in America in the 21st century is truly a choice,” he said. What this means is that organizations are feeling more pressure than ever to make Judaism seem attractive to young people—the future depends on it. “There should be no question to you or to those who read your work about our commitment to building Jewish families, Jewish marriages, Jewish relationships, that are core to the long-term growth and flourishing of the Jewish people,” Fingerhut said.

Adding to the trickiness of the situation, donors are getting worried. “Our donors want the Jewish community to be strong—that’s why they invest in us,” said non-denominational BBYO’s Grossman. “They’re concerned about the relationships that our kids are having with each other.”

“I think everybody’s concerned about the trend,” the Orthodox rabbi, Micah Greenland, said. “Everybody is concerned among our stakeholders.”

In brief, here’s the situation: Overall, millennials have doubts about getting married. If they do want to get married, they think it’s fine to marry someone of another race. If they’re Jewish, they’re more likely than ever to have a non-Jewish spouse, especially because many grew up with a non-Jewish parent. And if they don’t marry a Jew, they’re much less likely to raise Jewish kids.

Across the spectrum of observance, youth group rabbis want to welcome these kinds of students. They certainly don’t want to alienate them with oppressive lectures about the importance of dating other Jews.

But they do kind of want them to get the hint.

This is why the question of intermarriage among Jews is so fraught, especially given the recent discussion stirred by the Pew study. Every commentator has an opinion on the alleged assimilation of the Jewish people, but few are willing to argue outright that the future of American Judaism largely hinges on who today’s twenty- and thirtysomethings choose to marry and have children with. Millennials will determine how the next generation of Jews feels about heritage and faith, but leaders and journalists are shy about engaging them in explicit conversations about race. Perhaps this is for good reason, given how those conversations look to non-Jews and Jews who don’t share this ethnic view of Judaism.

The idea of “marrying to preserve one’s race” seems thoroughly at odds with the ethnically accepting, globally aware values of the Millennial generation. But rabbis will keep pitching them on why their marriage choices matter.

“It certainly is one of our 613 commandments, is to marry somebody Jewish,” said Greenland. “But on a much deeper level, it’s about engagement in Jewish life.”

“Look, I’m a rabbi,” said David Levy, who works with the Conservative USY. “But I believe the Jewish community has a unique, special, and powerful message for the world, and it’s one that deserves continuance for the world.”

“But I’m a little biased,” he added. “I’ve bet my life’s career on this.”